France and Sri Lanka: The dangers of cohab politics

Sri Lanka’s political crisis following the February 10 local polls election setback for the ruling coalition has brought to surface the vagaries of political cohabitation peculiar to the presidential cum parliamentary governments or hybrid governments.

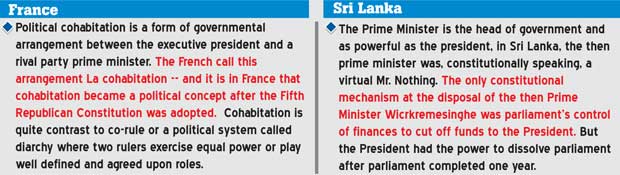

Political cohabitation is a form of governmental arrangement between the executive president and a rival party prime minister. The French call this arrangement La cohabitation — and it is in France that cohabitation became a political concept after the Fifth Republican Constitution was adopted. Cohabitation is quite contrast to co-rule or a political system called diarchy where two rulers exercise equal power or play well defined and agreed upon roles. Cohabitation is also different from constitutionally defined power-sharing arrangements as seen in the Northern Ireland power sharing deal where the Protestant first minister and the Catholic Deputy First Minister wield equal powers. In countries such as Iraq and Lebanon, power sharing is exercised on ethnic basis, with the presidency, the premiership and the post of Speaker being distributed among leaders of different ethnic groups.

In the absence of clear constitutional provisions, cohabitation governments are usually associated with political instability. This is because the president and the prime minister are often engaged in a political cold war to undermine each other. Often, cohabitation governments crumble under political manipulations, even if constitutional safeguards exist to check moves by the President or the Prime Minister to weaken each other.

In Sri Lanka, cohabitation became a political reality for the first time in 2001, when the then President Chandrika Kumaratunga dissolved parliament and called for general elections, only to see her rival Ranil Wickremesinghe’s United National Party polling 45.62 percent of the registered votes and winning the elections. Kumaratunga grudgingly swore in Wickremesinghe as prime minister. But the President felt uncomfortable sitting with her rival party leader and ministers at Cabinet meetings which she presided as the head of the Cabinet. Being a leader of a political party and her executive powers pruned by the prime ministerial rule, Kumaratunga planned to dissolve the Government at the very first opportune moment that came her way.

Unlike in France, where the Prime Minister is the head of government and as powerful as the president, in Sri Lanka, the then prime minister was, constitutionally speaking, a virtual Mr. Nothing. The only constitutional mechanism at the disposal of the then Prime Minister Wicrkremesinghe was parliament’s control of finances to cut off funds to the President. But the President had the power to dissolve parliament after parliament completed one year. Yet by getting the Speaker to entertain a petition to impeach the president, the premier could have prevented the president from dissolving parliament. Wickeremsinghe, however, rejected his party seniors’ advice to impeach the president, probably because he was too much of a gentleman politician or he believed if a general election was held, his party could win.

In retrospect it appeared that Kumaratunga had outfoxed Wickremesinghe. She dissolved parliament, disregarding a pledge she gave in writing to the Speaker that she would not dissolve parliament as long as the Prime Minister commanded the confidence of the majority in the house. This was power politics of Machiavellian type.

The constitutional provision with regard to the dissolution of parliament underwent a progressive change with the passage of the 19th Amendment in April 2015. Under this amendment, the President can dissolve parliament only after parliament completes four years and six months of its five year term. The amendment, among other things, also curtails the president’s power to remove the prime minister.

Notwithstanding the 19th Amendment’s checks on the presidential powers, President Maithripala Sirisena appears to take an upper hand in the present crisis engulfing the cohabitation government, which, unlike in France, is also a coalition government, sometimes called a national unity government by two rival parties which coexist despite regular conflicts. The fact that the prime minister’s party lacks a clear majority in parliament and that its public standing has taken a beating due to its failure to fulfill its campaign pledge to bring in good governance have enabled the president to call the shots and shoot down proposals from the prime minister’s party – proposals which if implemented could make the premier popular.

Sri Lanka’s cohabitation politics smacks of political skullduggery. Our politicians are even averse to bipartisanship for a national cause such as finding a solution to the national question. The collapse of the 2011 Liam Fox agreement between Kumaratunga and Wickremesinghe and the 2006 memorandum of understanding between the United People’s Freedom Alliance and the United National Party only confirm that our politicians give more priority to party politics than to national causes.

The recent events probably indicate that President Sirisena also awaits the Kumaratunga moment to stab Wickremesinghe in the back, though it was Wickremesinghe’s party that catapulted him to the president’s office. This is nothing uncommon in cohabitation politics. It happens even in France which tried out the first cohabitation government in 1986 with Socialist President Francois Mitterrand as president and the right wing Republican Party leader Jacques Chirac as prime minister. Mitterrand kept the portfolios of foreign, defence, nuclear strategy and European Union affairs while Chirac took charge of the economy and domestic affairs. In this arrangement, Mitterrand often interfered when the government was in a difficult situation. As a result, the prime minister took all the flak and became unpopular while the president’s star was on the ascent. Well, in Sri Lanka, too, this is happening. The SAITM issue and the controversy surrounding a brigadier attached to Sri Lanka’s High Commission in London are cases in point, where the UNP is seen as the villain and the president the trouble shooter and patriot.

France’s first cohabitation experiment lasted only two years. Mitterrand dissolved the government in 1988 and his party won the subsequent presidential and assembly elections. France also had cohabitation governments in 1993 and 1997. Of these cohab governments, the most acrimonious was the 1997 arrangement where Chirac was the president and the socialist politician Lionel Jospin was prime minister. Chirac alluded to the period as ‘political paralysis’.

The French experience shows, that after every cohab government, the president’s party wins the next election. In Sri Lanka, however, President Sirisena’s opportunity has been usurped by the Joint Opposition’s de facto leader and former president Mahinda Rajapaksa. Only Sirisean is to be blamed for this state of affairs, because he failed to take effective control of his party and crack the whip on dissidents when he was seen to be powerful. If he had done that, he could have by now become a formidable candidate for the 2020 presidential election, with the cohab government’s prime minister taking the blame for failures.

In this regard, the premiership appears to be disadvantageous to Wickremesinghe, unless he believes that holding on to the post will enable him to execute a well-thought-out plan to outfox his rivals. But the issue is his rivals also have big plans for 2020 polls.